In the world of nutrition, few topics spark as much debate and confusion as carbohydrates. Many people, frustrated by conflicting diet advice, end up treating carbs like an enemy to be avoided entirely. But the reality is that complex carbohydrates are the most effective and efficient source of fuel for human performance, both physical and cognitive. If you often experience that frustrating mid-afternoon energy crash, the culprit isn’t necessarily carbs themselves—it’s the type you’re choosing. This guide cuts through the noise, defining what carbohydrates are, how they function, and how prioritizing quality can dramatically improve your energy, mood, and long-term health.

The Chemical Foundation: Defining Carbohydrates as Essential Macronutrients

Before we can effectively choose what we eat, we need to understand what we are eating at a fundamental level. Carbohydrates are not a single food group; they are a class of organic compounds essential for life, falling into the category of macronutrients—nutrients the body requires in large amounts. This scientific foundation is crucial for making informed, sustainable dietary choices.

What are Macromolecules? Placing Carbohydrates alongside Fats and Proteins.

Macronutrients are the building blocks and energy suppliers of our diet. There are three primary types: proteins, fats (lipids), and carbohydrates. While proteins are the structural workhorses (building muscle, tissue, and enzymes) and fats are critical for hormone regulation and long-term energy storage, carbohydrates serve as the body’s preferred and most readily available energy source. Think of them as the high-octane gasoline for your daily drive, whereas fat is the diesel—essential, but less quick to ignite.

The Chemical Structure: Carbon, Hydrogen, and Oxygen in Starch and Sugar.

The name “carbohydrate” literally means “hydrated carbon.” Chemically, all carbs are composed of varying ratios of three elements: Carbon (C), Hydrogen (H), and Oxygen (O). These atoms link together to form sugar units. Simple sugars exist as single or double units (like glucose or sucrose), while starch and dietary fiber are much longer chains, sometimes containing thousands of these units linked together. It is the complexity and length of these chains that determines how fast or slow they release energy into your system.

Digestion Basics: How the Body Breaks Down Carbs into Absorbable Glucose.

The primary goal of carbohydrate digestion is to break down these complex structures into their smallest, most basic unit: glucose. This is the only form of carbohydrate that the body’s cells, especially the brain and muscles, can readily use for immediate energy. Enzymes in the mouth and small intestine dismantle the larger starch molecules into smaller sugars, which are then absorbed through the intestinal wall and transported via the bloodstream, signaling the release of insulin.

Decoding the Types: Simple vs. Complex Carbs and Their Metabolic Impact

Understanding the classification of carbohydrates is the key to mastering your energy levels. The distinction between simple and complex isn’t about morality (good vs. bad); it’s about molecular structure and the resulting metabolic timeline—how quickly the body can process and utilize the glucose.

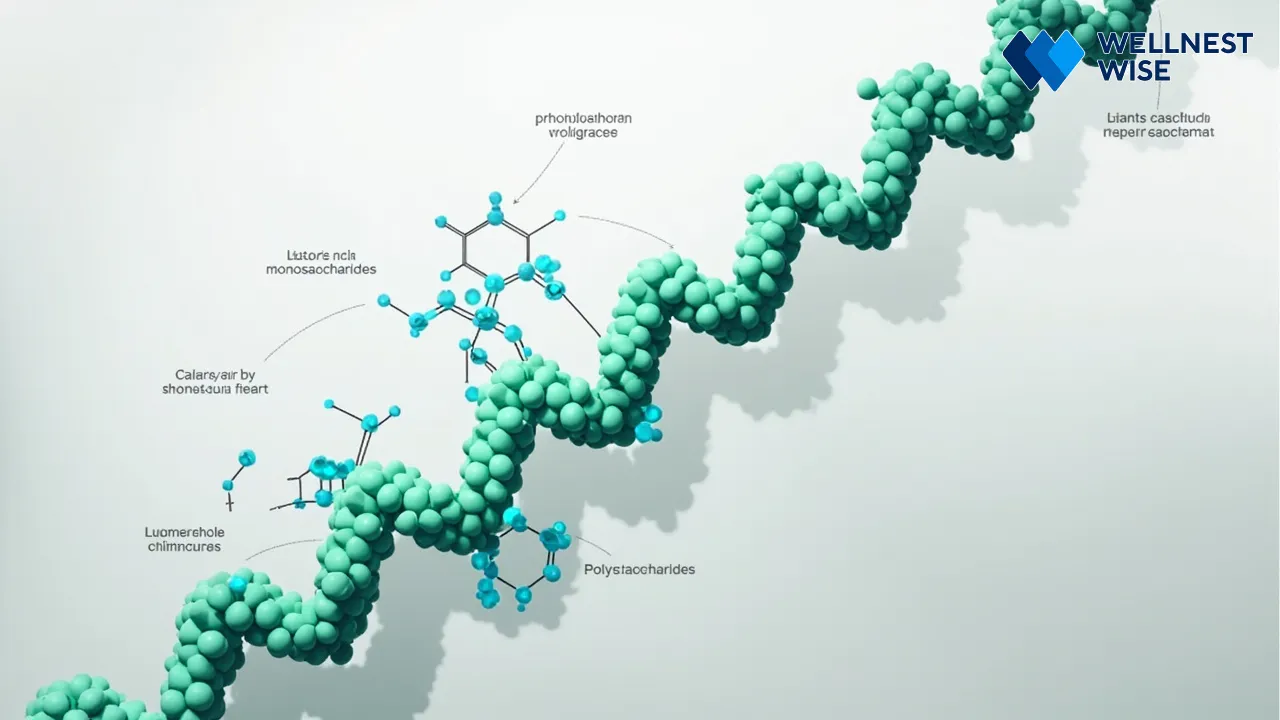

Simple Carbohydrates: Understanding Monosaccharides (Glucose, Fructose) and Disaccharides.

Simple carbs are sugars, defined by having one or two sugar units.

- Monosaccharides (single sugars) include glucose (primary energy fuel) and fructose (found in fruit and honey).

- Disaccharides (double sugars) include sucrose (common table sugar, made of glucose + fructose) and lactose (milk sugar).

Because they are small and require minimal breakdown, simple carbs are absorbed rapidly, causing a quick, sharp rise in blood glucose levels.

The Role of Glucose in Instant Energy Delivery.

When you consume simple carbohydrates, they enter the bloodstream almost immediately as glucose. This triggers a fast and significant insulin response designed to move the excess glucose into cells for use or storage. This rapid influx is useful during intense exercise or when treating hypoglycemia, but in daily life, it often leads to a quick energy peak followed by a crash.

Complex Carbohydrates: Polysaccharides, Starches, and Long-Chain Structures.

Complex carbohydrates (or polysaccharides) are long chains of sugar units linked together. These include starches found in grains, potatoes, and legumes, and dietary fiber found in plant cell walls. Since they are structurally large, the body must spend significant time and energy breaking them down.

This extended digestive process ensures a slower, more gradual release of glucose into the bloodstream, leading to stable energy and a gentler insulin response. This is why eating a bowl of oatmeal keeps you feeling full and focused longer than drinking a sugary soda.

The Critical Distinction: How Processing Affects the Release Rate and Insulin Response.

The nutritional quality of a carbohydrate is often determined by its level of processing. A whole food, like a kernel of wheat, is a complex carbohydrate surrounded by a fibrous coating. When manufacturers refine that wheat into white flour, they remove the fiber, turning the complex, slow-digesting starch into a product that behaves metabolically like a simple sugar, causing a faster insulin response. Choosing minimally processed, whole-food sources is therefore essential for metabolic health.

The Primary Fuel Source: Understanding the Function of Carbohydrates in Energy and Cognition

Contrary to the narrative that fats or proteins should dominate, carbohydrates are the most vital source of energy for the systems that matter most: movement and thought. Without adequate carb intake, both physical performance and cognitive function suffer.

Carbs as the Body’s Preferred Energy Source for Daily Activity.

Every gram of carbohydrate provides 4 kilocalories (kcal) of energy, making it an incredibly efficient fuel. For any activity requiring rapid energy—be it running, lifting weights, or simply walking briskly—your body preferentially taps into glucose. While fats store more energy per gram, the metabolic pathway to access that energy is slower and requires oxygen, making carbs crucial for quick action.

Fueling the Brain: Why Consistent Glucose Supply is Crucial for Cognitive Function.

Your brain, despite accounting for only about 2% of your body weight, consumes roughly 20% of your total energy intake, and its primary fuel is glucose. Unlike muscles, the brain cannot efficiently store energy or use fat directly (ketones are an alternative fuel, but glucose is preferred). A steady supply of glucose, delivered from the slow breakdown of complex starches, is necessary to maintain concentration, memory function, and stable mood. Without it, you feel foggy, irritable, and unable to focus.

Storage Mechanism: Converting Glucose into Glycogen Reserves in Muscles and Liver.

When you consume more glucose than your body needs immediately, it doesn’t just disappear. The body efficiently stores this energy in two places:

- Liver Glycogen: Maintains steady blood sugar levels, releasing glucose when needed (e.g., while you sleep).

- Muscle Glycogen: Used exclusively by the muscles for rapid energy during physical exertion.

These stored forms of carbohydrate, called Glycogen, ensure that you have reserves ready for intense effort or periods between meals.

The Role of Carbohydrates in Sparing Muscle Tissue from Breakdown.

One critical, often overlooked function of adequate carb intake is its muscle-sparing effect. If the body doesn’t have sufficient readily available glucose from your diet or glycogen stores, it will initiate gluconeogenesis—the process of creating glucose from non-carbohydrate sources, typically protein. This means the body starts breaking down amino acids, often pulled directly from muscle tissue, just to meet the brain’s demand for energy. Eating enough quality carbs prevents this catabolic state.

Quality Matters: Distinguishing Nutrient-Dense Carbs from Refined Sugars

The greatest health challenges related to carbohydrates stem from consuming highly refined, low-quality sources that lack essential nutrients. Prioritizing quality means looking beyond the caloric content and focusing on the presence of fiber and other vitamins.

The Importance of Dietary Fiber: Benefits for Satiety and Gut Health.

Dietary fiber is the undigested portion of plant food and is arguably the most beneficial component of complex carbohydrates. Fiber, which is also a type of carbohydrate, comes in two forms:

- Insoluble Fiber: Acts as roughage, adding bulk to stools and promoting regular bowel movements.

- Soluble Fiber: Dissolves in water, forming a gel that slows digestion, aids in satiety (feeling full), and helps lower LDL cholesterol.

Furthermore, fiber serves as food for beneficial bacteria in the gut microbiome, which is strongly linked to immune health and metabolic regulation. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), consuming adequate portions of fruits and vegetables—key sources of fiber—is vital for reducing the risk of noncommunicable diseases [4].

Understanding the Glycemic Index (GI): Speed of Absorption and Blood Sugar Control.

The Glycemic Index (GI) is a ranking system that measures how quickly a food raises blood glucose levels after consumption. Foods with a high GI (like white bread or refined sugars) cause a rapid spike, while low GI foods (like lentils or whole apples) cause a slower, steadier rise. Opting for low-to-medium GI foods is a practical strategy for maintaining stable energy, managing appetite, and supporting long-term metabolic health.

Hidden Sugars: Identifying Refined Carbohydrates and Added Sweeteners in Processed Foods.

Many highly processed foods contain significant amounts of “hidden” simple sugars and refined carbohydrates that are detrimental to health. Common culprits include high-fructose corn syrup, dextrose, and maltose, which manufacturers use to improve flavor, texture, and shelf life. Learning to read ingredient labels and identifying these added sweeteners is essential, especially given that diets high in free sugars are linked to increased risk of obesity and metabolic syndrome [4].

Are All Sugars Bad for You? Natural vs. Added Sugars in Fruits and Sweets.

The sugar found naturally in whole fruit (primarily fructose and glucose) is fundamentally different from added sugar in a candy bar. In fruit, the sugar is encased in water and a protective matrix of dietary fiber, vitamins, and antioxidants. This fiber slows digestion and absorption, mitigating the negative metabolic impact. In contrast, added sugars, when isolated and consumed without fiber, are absorbed too quickly, stressing the body’s insulin response system.

Strategic Intake: Optimizing Carbohydrate Choices for Sustainable Health and Gut Well-being

Optimal health doesn’t require eliminating carbohydrates—it requires smart choices. By prioritizing whole, unprocessed sources, you maximize nutrient delivery, fiber intake, and energy stability.

Prioritizing Whole Grains, Fruits, and Legumes: A Guide to Whole-Food Sources.

To maximize your nutritional return and ensure stable energy, focus on foods that maintain their natural form:

- Quinoa: A complete protein and high-fiber grain that provides long-lasting satiety.

- Barley: Rich in beta-glucans, a type of soluble fiber that is excellent for heart health and lowering cholesterol.

- Lentils and Chickpeas (Legumes): These are nutrient powerhouses, providing resistant starch, high protein, and a very low Glycemic Index, leading to exceptionally stable blood sugar.

- Berries (e.g., Blueberries, Raspberries): Offer a healthy dose of fiber and powerful antioxidants with a lower sugar load compared to tropical fruits.

- Oats (Steel-Cut or Rolled): A great source of soluble fiber, excellent for breakfast as they provide sustained energy well into the morning.

Recommended Daily Intake: Guidelines for Achieving Stable Energy (EEAT Focus).

While individual needs vary drastically based on activity level (an endurance athlete needs far more than a sedentary worker), general guidelines suggest that carbohydrates should make up approximately 45–65% of your total daily caloric intake. For the average person seeking stable energy, the key is ensuring the majority of that percentage comes from whole, unrefined sources.

(Personal Insight): My own shift to a diet emphasizing complex carbohydrates—primarily whole grains, legumes, and diverse vegetables—led to a marked increase in sustained energy throughout the day, fewer blood sugar spikes, and noticeably improved digestion. This personal adjustment strongly supports the scientific consensus that prioritizing quality over quantity in carbohydrate intake is the most effective approach to metabolic health.

Navigating Myths: Addressing Concerns About Carbs and Weight Management.

The myth that carbohydrates inherently cause weight gain is persistent but misleading. Weight gain results from a sustained caloric surplus, regardless of the macronutrient source. Diets high in refined carbs often lead to weight gain because these foods are low in fiber, lack satiety, and are easy to overconsume (think chips, cookies, white bread). When you replace refined carbs with high-fiber complex carbs, you naturally feel fuller longer, making calorie control easier and supporting healthy weight management [1].

A Comparative Look: The Nutritional Difference Between Starch, Fiber, and Simple Sugars.

The table below summarizes the crucial differences between the main types of carbohydrate components and their impact on your body.

| Component | Source Type | Digestion Speed | Impact on Blood Sugar | Primary Health Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| :— | :— | :— | :— | :— |

| Starch | Whole Grains, Tubers | Moderate/Slow | Moderate, Sustained Rise | Provides sustained energy reserves |

| Soluble Fiber | Oats, Beans, Apples | Very Slow | Minimal | Lowers Cholesterol and stabilizes glucose |

| Insoluble Fiber | Wheat Bran, Nuts, Skins | None (undigested) | None | Promotes bowel regularity and gut health |

| Glucose/Simple Sugar | Sweets, Honey, Soda | Very Fast | Rapid Spike | Instant energy (only for short bursts) |

Conclusion & Takeaways

Carbohydrates are fundamental to a healthy, energetic life. They are not dietary villains, but essential macronutrients that serve as the body’s fastest, most efficient source of fuel, powering your muscles and, crucially, your brain. The science is clear: the goal is not elimination, but optimization. By strategically replacing refined sugars and white flours with nutrient-dense, fiber-rich sources like whole grains and legumes, you gain control over your energy levels, improve gut health, and establish a dietary pattern that supports long-term well-being. Start small—try swapping white rice for brown rice or a refined breakfast cereal for a bowl of steel-cut oats, and notice the difference stable energy makes.

*

FAQ

How many carbs should I eat daily for stable energy?

There is no single magic number, as intake depends heavily on activity level, body composition, and overall health goals. For most adults, health organizations recommend that carbohydrates account for 45–65% of total daily calories. A highly active individual, like a marathon runner, might need closer to 60%, while someone with metabolic syndrome might aim for the lower end, prioritizing sources very high in dietary fiber (like vegetables and legumes) to manage insulin response.

Do complex carbs really prevent weight gain?

Complex carbohydrates themselves do not prevent weight gain, but they significantly aid in weight management. Because they contain high amounts of fiber, they are digested slowly, leading to greater satiety and reducing the urge to snack between meals. This improved feeling of fullness helps naturally lower overall daily caloric intake, which is the primary driver of sustainable weight loss.

What is the difference between starch and sugar?

Both starch and sugar are types of carbohydrates, but their chemical structures differ dramatically, affecting digestion. Simple sugar (like glucose) is a short, single, or double molecule that is rapidly absorbed, causing a quick rise in blood sugar. Starch is a long, complex chain of hundreds or thousands of sugar units linked together. The body must expend time and energy breaking down these long chains, resulting in a much slower, more stable release of glucose and a gentler insulin response.

Are all sugars bad for you?

No. Natural sugars found in whole fruits and vegetables are packaged with fiber, vitamins, and minerals that mediate their absorption. Added sugars and refined sweeteners, however, are empty calories devoid of nutritional value or fiber, leading to rapid energy spikes and potential metabolic stress. Prioritizing fruit over processed sweets ensures you get the energy from the sugar along with the necessary fiber to slow its delivery.